After the coronavirus crisis, many industries will have to change the way they operate, as people change their thinking about health, safety, travel & leisure and reassess their priorities.

What is in store for Higher Education?

Will this sector be „disrupted” as well?

Overview for „fast academics”:

The crisis has given new currency to grand questions of Higher Ed.

Online teaching infrastructure is finally used! 🙂

Access to online teaching is unequal! 🙁

Do we trust people to do a good job?

Beware of zoom bombs and video-lecture theft!

Mission of academics in post-truth era.

Will youtube lectures replace uni staff?

The coronavirus as a chance to reboot the academic system!

Grand questions of Higher Ed

The corona crisis is affecting Higher Ed differently in different countries. It brings out the strengths and weaknesses of the respective academic systems.

Because of the reliance on technology, there is a real risk that access to broadband and teaching platforms will make all the difference to students’ experience. So in many cases, it boils down to €$£. But there is a huge human factor as well. The coronavirus has given a new currency to the grand questions of Higher Ed sector:

- what do we want to teach?

- who will be able to study?

- who will own the knowledge?

- who will pay for education and who will be payed for it?

Online teaching: different speeds

Online teaching is developing at different speeds at different institutions and countries, depending on the available resources.

Some institutions have long been using elements of online teaching, so the necessary infrastructure was just sitting and waiting. When the coronavirus hit, everything was about ready to shift online. Everything but not everybody. So, crash-courses were swiftly organized to update staff on the myriad available tools. Despite some initial anxiety, at many institutions the transition to an online learning environment was almost seamless.

Where the technology is available, all forms of teaching are going ahead, from one-on-one tutorials through to conferences for hundreds of people!

Lectures, with the one-way communication between tutor and students are the easier format, despite some glitches due to video lag and lack of real-time verbal and non-verbal responses from participants. But teaching platforms can even enable seminars and workshops. For instance, some allow the tutor to allocate students randomly to groups and listen in during groupwork. At the end, students can carry out plenary presentations. Additionally, there are discussion boards, chats etc.

Even assessment was moved online, though with necessary adjustments (like forms of open book examination or projects instead of exams). The main platforms in use are: Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Blackboard Collaborate for online teaching and Media Hopper for editing recordings.

One positive outcome of this unprecedented shift to online teaching is that everyone had to get acquainted with these tools. Before some people were slow to take on the technology, perhaps thinking they might get by without it.

Meanwhile in the provinces…

The picture I’ve painted above applies to the realities of (some) British universities, with their “student-oriented”, “managerially-led”, “cutting-edge” etc. culture. In sharp contrast to this is the situation at less well-to-do institutions around the world (and in the UK!) which are forced to rely on more basic resources.

Without the access to specialised conferencing platforms, some teachers resort to posting their lectures on youtube and some can only upload files (like book chapters or power points) to online depositories. This makes for a much more passive learning experience.

In theory, students can contact tutors via email, but many just don’t. And in some cases, it’s the tutors who evade contact.

Before rushing to denounce the laziness of those who don’t engage in online learning and teaching, we should take a look at the resources they have at their disposal. Do teachers have the necessary equipment to deliver the kind of teaching which is expected of them? Can students easily access these resources?

Some universities have told academics who don’t have a good internet connection to use the campus wifi while working from their cars! That is assuming they have cars and quality laptops! Some students don’t have access to a computer or have to share it with a sibling or a working parent (or a child, in the case of mature students). In some areas the internet is too slow to follow an online session. So it’s back and sending coursework back and forth via email… (if the teachers and students are willing).

It’s all about trust

Online teaching requires a relationship of trust.

The tutor needs to trust their students to listen to the lecture (rather than turn it on and leave the room), to do their coursework, to not take advantage of the situation to justify missing deadlines etc. Similarly, management needs to trust academics to deliver quality teaching. And not all managers have been willing to give up their favourite hobby of micro-managing employees. I heard of one dean who holds daily one-hour-long skypes with faculty so everyone can brief him about what they have been up to. „Er…besides reporting to you?”.

How we deal with issues of trust in online teaching sheds light on the underlying relationship between members of an academic community. Do we see students and tutors as collaborators in the common quest for knowledge? Do we see managerial staff as facilitating this process? Or on the contrary, do we expect people to take advantage and cheat?

Who owns the knowledge (pst… it’s Google!)

Many of the platforms which are in use for online teaching are free, in theory offering access to all. This is of course an illusion. A free license usually imposes limitations as to the number of users, time of use and available features. As we know, “if something is free then you are the product”. So there is a question of tracking traffic and data use. And then there are the security lapses.

Apparently, strangers can drop ‘photo’ or ‘video-bombs’ with (sometimes) obscene images in non-encrypted Zoom sessions!

These are all reasons for the institutions to invest in a full licence for the service. This can be a big expense for universities (particularly smaller institutions in developing countries). Going ahead with it may mean taking resources away from other services. A smart solution would be to invest in your own in-house platform. Indeed, it looks like University of Warsaw has taken this road! Well done, Alma Mater!

Regardless of the platform which lecturers are using, there remains the question who owns the copyright on the teaching materials and the videos – the tutors or the university?

There is a fear that the many online-teaching materials which are now being produced will be recycled. Unis may use them over and over again with new groups of students. This would reduce required hours of traditional teaching and enable cuts to staff numbers. And what is to stop someone from recording a „locked” videoconference and disseminating it without permission? Once again, it boils down to trust.

Beyond just teaching

Teaching is not all broadband, hang-outs, zoom and skype (as the previous paragraphs would make you believe). The best technology is no substitute for a good teacher. I can hardly imagine what it’s like being a student nowadays. Locked-down in your dorm with Internet as your only connection to fellow inmates. Or back with parents in your hometown (hundreds of) miles from your institution, university fading into a distant illusion… Asking yourself how your education will figure in tomorrow’s job market? What is the point of studying as the coronavirus disrupts the world as we know it? Where do we come from and where we are going?

Tuning into these questions is as important nowadays as delivering the “core teaching”. In the UK tutors were advised to organise some social interaction, to ease the students’ stress. Some lecturers take up current issues related to the virus in class, so that students have an opportunity to voice their anxieties. I’ve heard many heartening accounts of academics who are going above and beyond their duty during the crisis. They work hard to deliver the best learning experience under the circumstances (not to mention IT support and counselling services!) But there is another important responsibility resting on academics.

In the era of post-truth, academics have the duty to support science-based approaches to the epidemic and oppose the spread of fake news & „populist science”.

This pressing task should be incorporated into the teaching of many subjects, be it “STEM” or “SSH” ones!

The future learning experience

The fact that so much teaching has been shifted online in a matter of days raises the question: what is the point of moving to a different town/abroad to get a university education? There are of course things which cannot be done online. There’s labwork and certain research tasks in the library. What cannot be replaced is the camaraderie of a classroom, the functionality of a dedicated learning environment, the coziness of a nice library (mmmm) and the cultural advantage of exploring a foreign country with its academic culture.

But will that be enough to sustain the current model of higher education and to justify the need for ever-shinier university campuses? There is the question: when will it be safe to travel and how prospective students and parents will feel about this decision? Currently, students in England are paying full tuition fees (and many are covering rent too). There seems to be a growing sense of bitterns (“are we paying 9K a year to watch pre-recorded videos?”).

Attitudes are understandably different depending on how much a degree costs.

In England where the cost of a BA is almost prohibitive (9K a year and that’s for home students) students are more worried about getting “value for money”. Where Higher Education is free for students, like in Poland, there is much more of a 'wait and see’ approach. Students’ anxieties are more about longer-term job prospects, the economy, domestic politics etc. Lecturers in the UK face a much harder task proving to their students that they are still getting “what they paid for”.

Alternatives to traditional uni?

Meanwhile, platforms like EDX which offer free (or cheapish, if you want certification) online learning have been booming. In view of the looming recession, some may turn to them as an alternative to a traditional academic degree. Those who still want to go for the „real deal”, might be tempted to choose an education closer to home (maybe opting for a branch of a foreign university in their own country, like Coventry Uni in Wrocław) or take a remote degree (like the ones offered by Open university).

Future recruitment numbers, the financial stability of universities, changing attitudes to travel, the rise of new less labour-intensive forms of online teaching all contribute to academics’ worries as to the future of their profession.

The bigger picture

All of these issues are just part of the big picture. The coronavirus crisis with accompanying political developments have raised fears over the future of democracies and markets in general.

Whether we feel safe, how much money we have to spend, if/when boarders will open, what will the perceived importance of an education be – all this will shape the future of higher ed as much as existing technological resources.

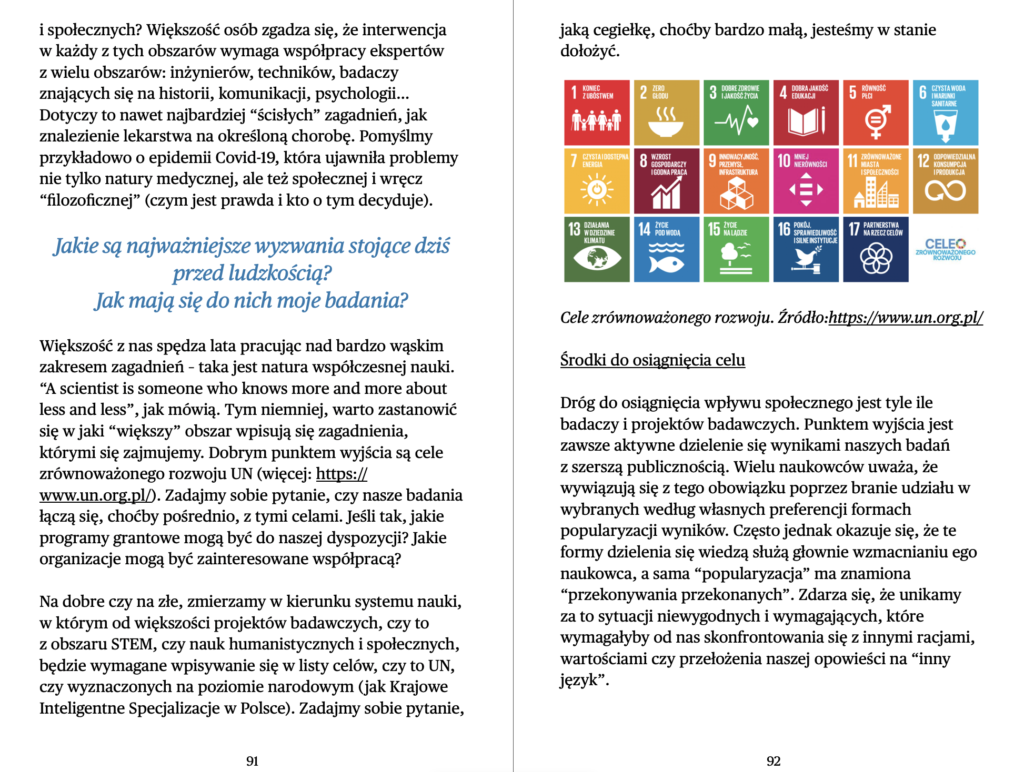

Some (optimists) see the coronavirus crisis as an opportunity to change the way we think about our environment and to embrace a more balanced, responsible and sustainable lifestyle. In the context of higher ed, I would much welcome a change in the dominant thinking about the role of universities in society.

The crisis is an opportunity to look at the value of university as going beyond delivering courses and distributing degrees.

Academia is a community of common goals, a quest for knowledge and progress. My hope would be that this crisis will allow us to reject the model of higher education as a product that one simply buys, of academia as a huge money-making machine, and of academic staff as disposable commodities. I only wonder if there is a way to achieve this without “rebooting” the whole system?

The coming weeks, months (years?) will bring many more reflections on how the coronavirus has changed higher ed.

I’m just not sure if my line manager (baby Wera) will allocate the time for me to write another post on the topic!

Aknowledgments

The above observations are based on exchanges with my good friends from university (Warwick University & Warsaw Uni – note I only study at institutions that start with “WAR”, haha) who are now teaching languages and linguistics at academic level around the world. I’ve also picked up points from Twitter threads and media (like this BBC 4 programme).

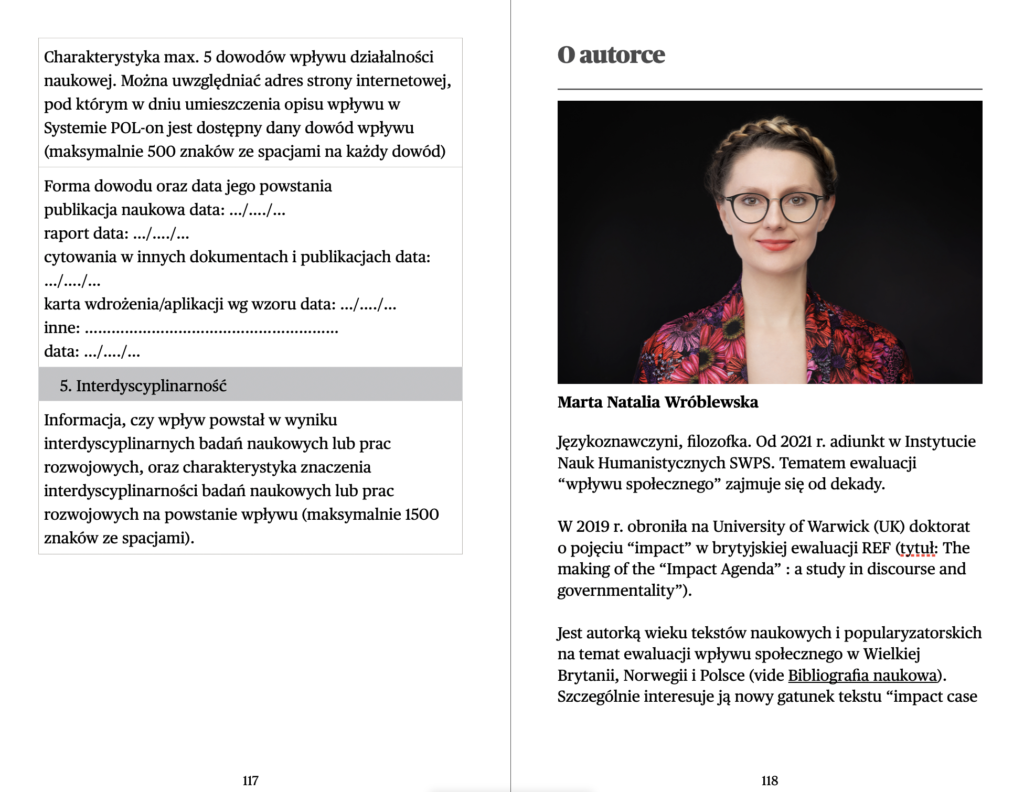

I want to thank my friends who shared their first-hand experiences with me. Thanks go to: Ana Salvi and Xristina Efthymiadou from universities in England, Samaneh Zandian from Scotland, Sixian Hah from Singapore, Zuleyha Unlu from Turkey, Michał Fedorowicz from Poland.